Creating Dr Reddy's Memorial mirrored our approach of minimal intervention—defining a space by celebrating existing elements on site and introducing a black reflective water body. Like crafting a story, we aimed to emotionally engage people in a journey through unfolding spaces, orchestrating an experience akin to the gradual build-up of a raga in Indian classical music, reaching a crescendo.

In this journey of realisation, every element played a pivotal role — the unfolding spaces, the play of light, the sound of water, the smell of grass, and the gentle breeze. The ritual of removing one’s shoes and touching Mother Earth became a fascinating sensory experience. The memorial transcends a physical structure, evolving into a journey of emotional resonance and introspection.

Anji Reddy Memorial

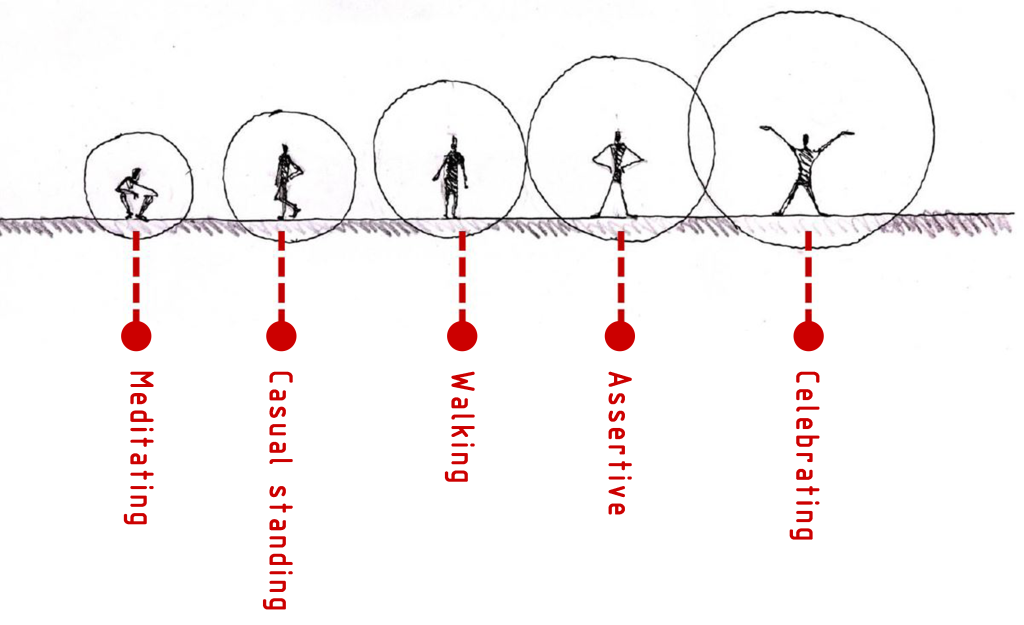

The concept of 'ownership' of open space evolved from simple fences to opaque compounds and ultimately, invincible fort walls. The detailing of these walls defining yards conveyed messages about fragility or strength, and reflected the owner's status - poor/rich, ordinary/special. The porosity of enclosure openings and yard gateways expresses dignity.

In designing the IISC library, there was a cluster of tall trees where the shade of their canopies could have become the library by itself. We had to just create an enclosure to preserve the tranquil environment where one can take a book, sit under the trees and feel connected with nature.

Planes wrapping around tree with activities at different levels

Scaling a space such that it ‘feels human’ has always been a priority, akin to the ethos found in Correa's earlier works like the Gandhi Ashram, Bharat Bhavan, and several houses. The skill of creating intimate spaces by experiencing larger volumes from low soffits is something we aimed to incorporate in our projects, such as the IISC library or Karunashraya.

Charles Correa Parekh's house | IISc library courtyard

Our climate has allowed us to explore these yards in various forms, blurring boundaries between built and unbuilt spaces, creating in-between threshold areas that seamlessly transition between being 'inside' or 'outside'. The teachings of Correa, Doshi, and Bawa guided us in crafting these ambiences. The climate dictates the shaping and sizing of these yards to allow the right amount of light, air, rain, and noise to filter in. For instance, courtyards in Kerala differ from those in Rajasthan due to climatic nuances.

Champalimaud by Charles Correa | IIMB by BV Doshi | Triton hotel by Geoffrey Bawa

Kerala house | Rajasthan house - section | Rajasthan House - Plan

Every climatic zone learned to embellish the yard, through the play of volumes, verandahs, levels, materials while also addressing climatic elements Screens, jaalis, and colonnades act as layers of defence against the harsh sun, emphasising the principles of controlling light, visual privacy, and bringing in breeze. Whether a small family home or a grand palace, the principles remain consistent, resulting in ingenious solutions across various scales.

Introducing water became a functional necessity, serving as a natural humidifier in hot, dry climates. For instance, a small fountain in the arid landscape of Rajasthan or cascading steps with pond water in the humid Kerala houses, create bathing ghats. In Kerala, the interplay of light reflecting off the water surface within these houses forms a magical and dynamic space.

Sketch: Section of space with fountain to water | Section of Kerala house adjacent to water | Image: Kerala house adjacent to water

Levels within the courtyard denoted social status as well. Head of the family or head of the village sitting at the higher level. This brought in an extra element of social and economic symbolism into the yard and demonstrated at a greater scale in the royal palaces. Similar symbolism is reflected subtly, in the way master bedrooms are placed in a house or the way teachers' room is placed in a school.

Sketch: Malnad house yard | Jaisalmer Public Square| Utsav house, Malnad | Jaisalmer Public Square

Symbolism is reflected in how activities unfold in different yards based on social needs, privacy, gender, and age group. It evolves throughout the day and the year. Lower-level activities may shift to rooftops during festivities like Makar Sankranti for kite flying, transforming terraces into elevated levels of action.

Sketch: Street-level activity | Terrace-level activity | Street-level activity | Terrace-level activity

The concept of a fence, initially born out of the primordial need for a man when he came out of a cave, led to the creation of yards—private ones attached to homes and public ones formed by clustering homes around a central point like a public well. The larger enclosure, often symbolized by celebrated gateways, evolved from mere fencing to formidable structures like fort walls or temple walls, as seen in the Tanjore and Srirangam temples.

Belapur Housing | CARE College, Trichy

The need for communication within families and across communities resulted in a hierarchy of open yards, from private to semi-private, semi-public, and public. This concept is exemplified in Charles Correa’s Belapur housing project. In a housing scheme for IISc in Bangalore, a similar idea was explored on a smaller scale, providing open-to-sky private areas for each apartment, and creating a series of open spaces with different dimensions and symbolic gateways. In this central yard, a couple of ‘tilted’ elements were added which gave different dynamism to the experience of the spine through minimal intervention.

Idea sketch | IISc housing Plan | IISc housing

Every religion has a deep-rooted way of establishing space to aid the process of praying, from the large central gathering space in a mosque with it’s surrounding walls and quibla defining orientation, to the series of courtyards and halls diminishing in size leading to the sanctum in a temple, culminating in a one-on one moment with the central deity.

Charles Correa describes this as the ritualistic path. To move along a path towards a sacred centre is a primordial experience, one so embedded in the deep structure of the human mind that it has appeared in almost every society since the beginning of time.

The commonality is that both have indoor and outdoor spaces mainly because climatic factors allow for it, but the way a person experiences them is almost entirely different.

The Japanese zen garden embodies the idea of the sacred through the behaviour of a person in the space. The placement of the stones, plants, the raking of the gravel and the position of sitting, all together.